Right to Read inquiry report

View and download PDF: Executive summary and key recommendations

On October 3, 2019, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) announced a public inquiry into human rights issues that affect students with reading disabilities in Ontario’s public education system. The Right to Read inquiry, which focused on early reading skills, found that Ontario’s public education system is failing students with reading disabilities (such as dyslexia) and many others, by not using evidence-based approaches to teach them to read.

The Right to Read inquiry report highlights how learning to read is not a privilege but a basic and essential human right. The report includes 157 recommendations to the Ministry of Education, school boards and faculties of education on how to address systemic issues that affect the right to learn to read. The report combines research, human rights expertise and lived experience of students, parents and educators to provide recommendations on curriculum and instruction, early screening, reading interventions, accommodation, professional assessments and systemic issues. Implementing the OHRC’s recommendations will ensure more equitable opportunities and outcomes for students in Ontario’s public education system.

More resources

- Executive summary

- Executive summary audiobook

- Full report

- OHRC recommendations to meet the right to learn to read

- Live stream: Right to Read inquiry report release

- Remarks by OHRC Chief Commissioner Patricia DeGuire

- News release

- Right to Read inquiry – community support

- Backgrounder: About the inquiry

- Backgrounder: What the community said

- Right to Read inquiry video

- Ministry of Education's response to the Right to Read report (accessible PDF)

- OHRC statement on Ministry of Education response to Right to Read report

- Stakeholder responses

- List of supports

- OHRC’s Right to Read inquiry work since 2019

Executive summary

View and download PDF: Executive summary and key recommendations

ISBN: 978-1-4868-5826-2 (Print)

978-1-4868-5827-9 (HTML)

978-1-4868-5828-6 (PDF)

Approved by the OHRC: January 27, 2022

WARNING: This summary deals with topics that may trigger some readers. It includes references to bullying, emotional and physical abuse, mental health challenges, self-harm and suicide. Please engage in self-care as you read this material. There are many resources available if you need additional support, including on the OHRC website at: www.ohrc.on.ca under List of supports.

Introduction

The right to equal education includes the right to read

On November 9, 2012, the Supreme Court of Canada released a unanimous decision recognizing that learning to read is not a privilege, but a basic and essential human right. The Supreme Court found that Jeffrey Moore, a British Columbia student with dyslexia, had a right to receive the intensive supports and interventions he needed to learn to read. The school board’s failure to provide special education programs and services, including intensive intervention, denied Jeffrey Moore meaningful access to education, resulting in discrimination under the British Columbia Human Rights Code. The Court said:

…adequate special education…is not a dispensable luxury. For those with severe learning disabilities, it is the ramp that provides access to the statutory commitment to education made to all children…

The Moore v British Columbia (Education) decision (Moore) confirmed that human rights laws in Canada protect the right of all students to an equal opportunity to learn to read. This decision was lauded as a significant victory for students with disabilities, particularly students with reading disabilities. Many hoped that it would act as a catalyst for systemic change in Ontario’s education system.

Almost 10 years after the Moore decision, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) released a report on its public inquiry into the right to read. The right to read applies to ALL students, not just students with reading disabilities. This inquiry found that Ontario is not fulfilling its obligations to meet students’ right to read.

Despite decades of multi-disciplinary research on what is most effective for teaching students early reading skills, and after Moore affirmed that meaningful access to education, including learning to read, is a human right, Ontario is systematically failing students with reading disabilities and many other students. The promise of Moore has not been fulfilled. This leaves many students at risk for significant life-long difficulties. The inquiry is not just about an equal right to read – it is about an equal right to a future.

|

The science of reading This report uses terms like the “science of reading,” “reading science,” “research-based,” “evidence-based” and “science-based” to refer to the vast body of scientific research that has studied how reading skills develop and how to ensure the highest degree of success in teaching all children to read. The science of reading includes results from thousands of peer-reviewed studies and meta-analyses that use rigorous scientific methods. The science of reading is based on expertise from many fields including education, special education, developmental psychology, educational psychology, cognitive science and more. |

Launching a public inquiry

The OHRC has a mandate to protect human rights and the public interest in Ontario and promote compliance with the Ontario Human Rights Code (Code). The OHRC does this by developing policies, initiating public inquiries, and engaging in strategic litigation. Although the OHRC does not have the same power as the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO) to make legally binding findings of discrimination or to order remedies, it has a unique power to hold systemic inquiries in the public interest (section 31 of the Code). This includes the power to request documents, data and information, analyze it with the help of experts and issue findings and recommendations. The information obtained in a section 31 inquiry may be used as evidence in a proceeding before the HRTO.

In October 2019, building on previous work on accessible education, including its intervention in Moore and its Policy on accessible education for students with disabilities, the OHRC launched a public inquiry into human rights issues facing students with reading disabilities in Ontario’s public education system. The OHRC worked with two experts in reading development and reading disabilities, Dr. Linda Siegel and Dr. Jamie Metsala, to analyze significant information obtained from a representative sample of eight English-language public school boards, all 13 Ontario English-language public faculties of education, and the Ministry of Education (Ministry).

The inquiry also heard from thousands of students, parents, organizations, educators and other professionals through surveys, public hearings, a community meeting, engagements with First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities, artwork, emails, submissions, meetings and telephone calls.

The inquiry, the first of its kind in Canada, combined the OHRC’s expertise in human rights and systemic discrimination with Dr. Siegel and Dr. Metsala’s expertise in reading development, reading disabilities/dyslexia, interventions to improve reading and the extensive body of research science.

|

School boards and faculties of education reviewed for the inquiry The eight sample English-language school boards selected for the inquiry were:

Ontario’s 13 English-language public faculties are of education were:

|

Focusing on early reading

Literacy goes beyond the ability to read and write proficiently. It includes the ability to access, take in, analyze and communicate information in a variety of formats, and interact with different forms of communication and technologies.

Word-reading and spelling are a foundation for being able to read and write and successfully interact with different forms of communication. Everyone wants and needs to be able to read words to function in school and life. The inquiry heard many accounts of people who could not read a menu in a restaurant, read ingredients on a food label, read street signs, play video games that involve reading, search the Internet, look at websites or access other forms of digital media.

Becoming fully literate also requires more than just the ability to read words. The ability to understand the words that are read and the sentences that contain them are important for strong reading comprehension. A comprehensive approach to early literacy recognizes that instruction that focuses on word-reading skills, oral language development, vocabulary and knowledge development, and writing are all important components of literacy.

The inquiry focused on word-level reading and the associated early reading skills that are a foundation for good reading comprehension. This focus was chosen because of the ongoing struggle for Ontario students to receive evidence-based instruction in these foundational skills; the difficulty in meeting early reading outcomes for many students, often from marginalized or Code-protected groups; research recognizing the importance of instruction in these foundational word-reading skills; and the recognition of the rights of students with dyslexia in the Moore decision.

Word-level reading difficulties are the most common challenge for students who struggle to learn to read well. Most students who have issues with reading comprehension have word-level reading difficulties.

Despite their importance, foundational word-reading skills have not been effectively targeted in Ontario’s education system. They have been largely overlooked in favour of an almost exclusive focus on contextual word-reading strategies and on socio-cultural perspectives on literacy. These are not substitutes for developing strong early word-reading skills in all students. The OHRC’s position is that making sure all children are taught the necessary skills to read words fluently and accurately furthers and does not detract from equity, anti-racism and anti-oppression.

Early word-reading skills are critical, but they are not the only necessary components in reading outcomes. Robust evidence-based phonics programs should be one part of broader, evidence-based, rich classroom language arts instruction, including but not limited to story telling, book reading, drama, and text analysis. Evidence-based direct, explicit instruction for spelling and writing are also important to literacy. Many students, including students with reading disabilities, have difficulties with written expression. Explicit, evidence-based instruction in building background and vocabulary knowledge, and in reading comprehension strategies, are all parts of comprehensive literacy instruction. Although the inquiry focused on one most frequent obstacle to students developing a strong foundation in early reading skills, the report also acknowledges the other elements of a comprehensive approach to literacy. These elements must also be addressed when implementing report recommendations.

Focusing on the Ministry of Education, school boards and faculties of education

The inquiry focused on the Ministry, school boards and faculties of education (faculties) because each has a central role in meeting the right to read. The Ministry has ultimate responsibility for education in Ontario. It sets the curriculum that Ontario teachers must teach. It can set out provincial standards, for example for assessment, evaluation and reporting, data collection and special education services, and require boards to follow them. The Ministry also funds education.

Ontario’s 72 public school boards deliver education services, including special education, in accordance with Ministry requirements. They also have significant discretion on how to spend funds and deliver services, including special education services.

Faculties have a key role in preparing teachers to teach students early reading skills, and in providing ongoing professional development in areas such as reading and special education.

Other education sector partners have important responsibilities in addressing the rights of students with reading disabilities. The Ontario College of Teachers (OCT) establishes requirements for teacher education programs for future teachers (also called pre-service teachers) and Additional Qualification courses for current teachers (also called in-service teachers). The inquiry makes recommendations about what pre-service and in-service teachers should learn about teaching reading and reading disabilities.

The Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) administers provincewide tests to evaluate the achievement of students with the goal of promoting accountability and continuous improvement in Ontario’s public education system. The inquiry makes recommendations related to EQAO data.

The Ontario Psychological Association (OPA) and the Association of Psychology Leaders in Ontario Schools (APLOS) establish guidelines for diagnosing students’ reading disabilities, and the inquiry makes recommendations to the OPA and APLOS about these guidelines.

The Right to Read report sets out the inquiry’s findings and 157 interconnected recommendations for these education sector partners on how to meet the right to read. Because the issues are systemic and require a consistent system-wide response, the report recommends that the Ministry work with an independent expert or experts to implement many of the recommendations. It will also be critical that the recommendations be implemented in their entirety, because together they form a holistic approach to the right to read. The OHRC also emphasizes that sufficient, stable ongoing funding will be needed to successfully implement these recommendations.

Although the inquiry’s primary focus was on English-language boards and faculties of education, it also identified challenges related to French-language education. Most inquiry findings and recommendations likely apply equally to French-language education and the OHRC expects that the Ministry and French boards will address and implement the recommendations as appropriate for students learning in French.

Background

Key findings and recommendations

This report uses both the terms reading disability and dyslexia. Currently, the Ontario education system only uses the term learning disability, which typically only includes students who have been formally identified with a learning disability through a process called an Identification, Placement and Review Committee (IPRC). The education system does not identify if the learning disability affects word reading or another area such as mathematics, and does not collect data about students who have not been formally identified. A lot of valuable information for planning and tracking is therefore lost.

The term “dyslexia” is also not used in the Ontario education system. However, the American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic or Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) recognizes dyslexia as an appropriate term for referring to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor decoding, and poor spelling abilities. After the inquiry was launched, the Ontario Psychological Association updated its Guidelines for Diagnosis and Assessment of Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Learning Disabilities to recognize the value of psychologists using the term dyslexia when making a diagnosis. Dyslexia is well researched and understood, and there are many helpful dyslexia resources. Some also prefer the term “dyslexia” as it indicates a learning difference, and are concerned about the socially-constructed stigma that may be associated with a “disability” label. Under the Code, people’s preferred self-identification should be respected and recognized.

| The OHRC recommends the Ministry, faculties of education and school boards explicitly recognize the term “dyslexia” [Recommendations 51, 54, 55, 56, 114, 126]. |

| The OHRC recommends that school boards identify and track students by the type of learning disability/academic area that is impaired (for example, identifying that a student has a reading disability instead of a learning disability) [Recommendation 126] and collect data specific to all students with reading disabilities (including students who have not been formally identified through an IPRC) [Recommendations 133, 135, 142, 143, 145, 148]. |

Reading disabilities and other barriers to learning to read

Dyslexia or a reading disability in word reading is a specific learning disability characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word reading and/or poor decoding and spelling abilities. These word-reading difficulties may also result in problems with reading comprehension and can limit learning vocabulary and background knowledge from reading. Dyslexia is the most common learning disability, and learning disabilities are the most prevalent special education exceptionality in Ontario. This means that dyslexia/reading disabilities are the most prevalent disabilities in schools. There are students with dyslexia/reading disabilities in every Ontario classroom.

Although dyslexia is assumed to be neurobiological in origin, there is evidence that with evidence-based reading instruction, early identification, and early evidence-based reading intervention, at-risk students will not develop a “disability.” If the education system is working as it should, a reading disability can be prevented for almost all students.

Students with other disabilities, including intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, and hearing disabilities, may also struggle to learn to read when ineffective approaches are used in the classroom. Because of marginalization and structural inequality, Black and other racialized students, First Nations, Métis and Inuit students, multilingual students, or students from low-income backgrounds are also at increased risk for reading difficulties. Approaches to teaching early reading that build skills for decoding words and language comprehension have been proven to work best for all students, and are essential for many students.

For most students, but particularly vulnerable students, reading outcomes depend on the quality of reading instruction they receive. Nearly all students can learn to read words proficiently with science-based systematic and explicit instruction in foundational reading skills. Identifying and intervening early with the small number of students who may still struggle to learn to read words well, sets them up for future success in school, work and life. But failing to prevent a word-reading disability in the vast majority of cases where this is possible, has serious life-long consequences. The research and lived experience accounts gathered in the inquiry show the negative trajectory of students who do not develop proficient early word reading skills.

What happens when students do not learn to read

Students who don’t develop good early reading skills can very quickly begin to experience negative academic consequences, which may only get worse. Reading is necessary for many aspects of learning in school, and initial difficulties can increase over time and impede accessing the curriculum in other subjects. This is one of several reasons why early intervention for struggling readers is essential.

When students have difficulty learning to read, it can affect their confidence in their academic abilities and overall self-esteem, and lead to significant mental health concerns. The inquiry heard many students describe themselves as “stupid” because they cannot read, even though reading disabilities have nothing to do with intelligence. Consistent with findings in the academic research, many students and parents told the inquiry about depression and anxiety, school avoidance, acting out, being bullied or victimized, self-harming, and thinking about or even attempting suicide.

Students with reading disabilities often underachieve academically. They are more likely to drop out of school, less likely to go on to post-secondary education, and tend to take longer to finish programs they enroll in. The effects can continue past their schooling and can have a negative impact on employment, and lead to lower incomes, poverty and homelessness and higher rates of involvement in crime and incarceration. Adults with dyslexia told the inquiry about long-term effects of not learning to read, such as mental health and substance abuse issues and negative impacts on their employment.

Broader impacts on families and society

Parents also reported impacts on the family, something that has also been described in the literature. Parents talked about the financial effects when families spent money on private assessments and tutoring, and gave up or changed their employment to have the time to support their child. Other family impacts included the challenges of navigating the school system, negative effects on relationships and significant mental health burdens.

The broader impacts of low literacy on society are also well documented, which is why many organizations advocate for improving literacy in Ontario, with a focus on foundational word reading skills. For example, the Pediatricians Alliance of Ontario (PAO) and the Physicians of Ontario Neurodevelopmental Advocacy (PONDA) have recognized the relationship between literacy and health outcomes, and have called for curriculum and reading instruction that incorporates explicit, systematic instruction in phonics, early screening and early evidence-based intervention. The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police has identified improving literacy as a tool to combat crime.

Reducing the social and economic costs of low literacy

Investment in early reading significantly reduces the social and economic costs of low literacy to the individual, their family and society as whole. It also improves equity outcomes. Children from groups protected under the Code disproportionately suffer the effects of failing to use evidence-based approaches to teaching reading and supporting struggling readers. Their parents do not always have the same access to resources and private supports as more advantaged parents. These students rely on the public education system to give them a strong foundation in reading to help reduce their historical and social disadvantage. When the education system does not do this, it can worsen their marginalization and risk of inter-generational inequality.

These significant burdens on individuals, families and society are preventable. Dr. Louisa Moats, an expert on science-based reading instruction and teacher education, said in Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science, 2020 that “the tragedy here is that most reading failure is unnecessary.” Decades of research shows us what we need to do to give all students equal opportunity to learn to read, but this knowledge has not translated into what is happening in schools.

What is needed to teach all students foundational word-reading skills

The key requirements to successfully teach and support all students are:

- Curriculum and instruction that reflects the scientific research on the best approaches to teach word reading. This includes explicit and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, which teaches grapheme to phoneme (letter-sound) relationships and using these to decode and spell words, and word-reading accuracy and fluency. It is critical to adequately prepare and support teachers to deliver this instruction.

- Early screening of all students using common, standardized evidence-based screening assessments twice a year from Kindergarten to Grade 2, to identify students at risk for reading difficulties for immediate, early, tiered interventions.

- Reading interventions that are early, evidence-based, fully implemented and closely monitored and available to ALL students who need them, and ongoing interventions for all readers with word reading difficulties.

- Accommodations (and modifications to curriculum expectations) should not be used as a substitute for teaching students to read. Accommodations should always be provided along with evidence-based curriculum and reading interventions. When students need accommodations (for example, assistive technology), they should be timely, consistent, effective and supported in the classroom.

- Professional assessments, particularly psychoeducational assessments, should be timely and based on clear, transparent, written criteria that focus on the student’s response to intervention. Criteria and requirements for professional assessments should account for the risk of bias for students who are culturally or linguistically diverse, racialized, who identify as First Nations, Métis or Inuit, or come from less economically privileged backgrounds. Professional assessments should never be required for interventions or accommodations.

Broader equity issues affecting student outcomes

The OHRC assessed Ontario’s current approach against these requirements. It also considered broader systemic issues related to these areas to determine if:

- There are consistent standards and approaches at the provincial and school board levels

- There is monitoring and accountability at the provincial and school board levels

- Boards and the province are collecting data to monitor individual student outcomes, support evidence-based decision-making, and analyze equity gaps based on disability; race; First Nations, Métis, Inuit ancestry; socio-economic status and other identity characteristics

- Boards are transparent in their communication with parents.

The OHRC also considered barriers faced by students with other disabilities and students from marginalized groups such as First Nations, Métis and Inuit students; Black and other racialized students; newcomer students; multilingual students; students from low socio-economic backgrounds; and students facing intersecting barriers (where several of these factors combine to create unique or compounded disadvantage).

| The OHRC makes specific recommendations to address these barriers, for example, to address the unique needs of First Nations, Métis and Inuit learners [Recommendations 1 to 26, 120] and multilingual students [Recommendations 62, 118, 124]. |

|

First Nation, Métis and Inuit children and youth experience unique challenges and barriers in accessing education. The ongoing legacy of residential schools; trauma; oppression, colonialism, racism and disadvantage; poverty (including inadequate housing, food insecurity and lack of access to clean water) and a lack of a feeling of belonging in school are some of the factors that have negative effects on First Nations, Métis and Inuit students’ education, including their experience in learning to read. The inquiry heard that many of the challenges faced by students with reading disabilities and their families are amplified for First Nations, Métis and Inuit:

While many of this report’s findings and recommendations will support First Nation, Métis and Inuit students’ right to read, particular attention needs to be paid to their intersectional needs to meet their substantive equality rights, treaty rights and their rights under international law (such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). |

Inquiry findings on reading outcomes in Ontario

Key findings and recommendations

Quantitative and qualitative data gathered in the inquiry shows an urgent need to improve reading and other student achievement outcomes in Ontario. Too many Ontario students are not learning to read well. Reading achievement for Ontario students is concerning, but the outcomes for students with special education needs (excluding gifted), learning disabilities, boys, Black and other racialized students, multilingual students, students from low-income backgrounds, and Indigenous students are even more troubling.

With evidence-based word-reading instruction, many more children can learn to read proficiently and enjoy reading in the earliest elementary grades. Built on these foundations and incorporating evidence-based instruction in all components of literacy instruction, they can be meeting provincial testing standards in Grade 3 and 6 and the Grade 10 Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test. They can also get all the other benefits that come from having strong reading skills and comprehension. The assumption that some students – including students with disabilities – will never learn to read well is a form of ableism. It is used to justify maintaining systemic barriers instead of making changes we know will help all students learn to read.

Although the inquiry analyzed some quantitative data, there is a need for improved data collection, analysis and reporting on reading and other student achievement outcomes. EQAO reporting should be more transparent and include more detailed information about students with special education needs, including on their success rates and use of accommodations. Better data is needed to see if other students also experience inequality in reading and other outcomes, to identify and close equity gaps. There is little or inconsistent data at a school board or provincial levels on streaming and post-secondary participation. Other concerns with data collection are discussed in several sections of the report, particularly section 13, Systemic issues.

| The OHRC recommends improving data collection, analysis and reporting in several areas [Recommendations 23 to 26, 55, 60, 63, 67, 81, 136, 137, 139 to 150]. |

The data confirms change is needed

The inquiry gathered quantitative and qualitative data on reading and literacy outcomes in Ontario. As school boards and the province do not collect other data on reading outcomes, the main source of quantitative data for the inquiry was EQAO reading test scores. The inquiry gathered qualitative data from a variety of lived experience accounts. Both the quantitative and qualitative data show more Ontario students are experiencing reading difficulties than should be.

With science-based approaches to reading instruction, early screening and intervention, we would expect to see only about 5% of students still below grade-level expectations on word-reading accuracy and fluency. However, in 2018–2019, 26% of all Ontario Grade 3 students and 53% of Grade 3 students with special education needs (students who have an Individual Education Plan (IEP), excluding students whose sole identified exceptionality is giftedness) were not meeting the provincial EQAO standard. Although the EQAO tests do not measure word reading accuracy and fluency separately, these significantly impact early reading comprehension. The results improved only slightly for Grade 6 students, where 19% of all students and 47% of students with special education needs did not meet the provincial standard.

The inquiry found similar results in the eight school boards. Far too many students with special education needs in these boards were unsuccessful on the Grades 3 and 6 2018–2019 EQAO reading assessments. When looking specifically at students identified with a learning disability exceptionality, in most boards, only about half of students with a learning disability exceptionality were able to meet provincial EQAO standards, even with a high rate of accommodations.

The data doesn’t show the true extent of the problem

The success rates on EQAO reading assessments are even more troubling when considering that most students with special education needs who meet the provincial standard use accommodations such as assistive technology to have the test questions read to them, and/or scribes to write down their answers. Accommodations are important and necessary for some students to access the curriculum and show their understanding of it. However, when looking at EQAO scores it is important to consider accommodations because when students use assistive technology or scribing, EQAO results do not tell us if those students can read or write unassisted.

Provincial and school board data from the eight inquiry boards shows that very few students with special education needs met the standard unaccommodated. For example, the International Dyslexia Association’s (IDA) report Lifting the curtain on EQAO scores found that in 2018–2019, only 8.5% of Grade 3 students with an IEP achieved the provincial standard on the EQAO reading assessment without using assistive technology or scribing. This is consistent with the OHRC’s findings from the school board data about students with identified learning disabilities. In 2018–2019, very few students identified with a learning disability exceptionality in the eight inquiry school boards met the provincial EQAO reading standard in either Grade 3 or 6 reading without accommodation.

The IDA report found little to no improvement in the unaccommodated pass rate for students with special education needs (excluding gifted) between 2005 and 2019 or for the reading achievement of all students in Ontario. The use of assistive technology and scribing accommodations has also been increasing over time.

In its 2018–2019 provincial report, the EQAO highlighted the underachievement of students with special education needs as a significant concern. It said:

The persistent discrepancy in achievement between students with special education needs and those without requires attention. EQAO data show that students with learning disabilities are the largest group in the cohort of students identified as having special education needs. Historically, students with learning disabilities have had a low level of achievement despite having average to above average intelligence. It would be beneficial to review supports available and strategies for success.

The EQAO data, which is already concerning, likely significantly under-represents the magnitude of reading difficulties among Ontario students. EQAO scores do not reflect whether the education system is equipping students to read independently.

Achievement gaps for Indigenous students

Unique and compounded forms of disadvantage contribute to an achievement gap between First Nations, Métis and Inuit students and other students. Some gains have been made in recent years. However, using EQAO scores, credit accumulation rates and graduation rates as measures, students who have voluntarily identified as First Nations, Métis or Inuit are still behind other Ontario students.

Provincial EQAO data and data from the inquiry school boards showed that students who have self-identified as First Nations, Métis and Inuit were less likely to meet the provincial reading standard. Five-year graduation rates for self-identified First Nations, Métis and Inuit students in provincially funded schools are also lower than provincial rates for all students.

First-hand accounts that many students struggle with reading

Qualitative data collected in the inquiry also included many examples of students failing to learn to read or only learning to read through significant effort and private services, where families can afford them. Students, parents, teachers and other professionals all provided examples of students many years behind in reading skills. Some students entering high school were reported reading at a primary level (Grades 1–3). Many educators acknowledged that this does happen and that when it does, the system has failed the student.

The EQAO also assesses students’ engagement with reading using a student questionnaire. In 2018–2019, fewer than half of students (44% in Grade 3 and 42% in Grade 6) reported they like to read. A significant proportion (38% in Grade 3 and 33% in Grade 6) said they do not think they are good readers most of the time. This suggests that current approaches to reading are failing to teach many students to read, and to promote reading confidence and a love of reading in many more.

Inequities in other student success indicators

The inquiry examined other student outcomes and found areas of concern. For example, there have been longstanding concerns about marginalized students being disproportionately steered or streamed into applied or locally developed high school courses, instead of academic-level courses. This negatively affects the student’s future academic pathways and opportunities.

School boards that collect and analyze demographic data have found that Indigenous, Black and Latin American students as well as students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are disproportionately represented in applied and locally developed classrooms. The inquiry found that students who have been identified with learning disability exceptionalities are also more likely to be streamed. In the inquiry boards, students identified with a learning disability exceptionality were about two to four times more likely to be taking mostly applied courses in Grade 9.

The inquiry also found that streaming happens in other ways and at a younger age. This includes placing students in special education classrooms where they do not receive appropriate interventions for their reading difficulties, or streaming them out of French Immersion programs instead of providing them with accommodations and interventions so they can remain in the regular classroom or in French immersion.

The inquiry was unable to assess potential inequities in other student outcomes. The inquiry boards were not able to provide any or consistent data on student success outcomes, such as graduation rates and post-secondary participation, for students with identified learning disabilities or other identity characteristics. For example, although the Ministry publishes overall graduation rates by boards, boards do not consistently track potential inequities in graduation rates for historically marginalized students. Boards can only disaggregate graduation data for students who graduate from the same school district they started their secondary schooling in.

Due to a lack of data, the inquiry could not confirm if students with learning disabilities are more likely to leave school without receiving their diploma, a trend found in the research. Only one inquiry board provided a report that analyzed achievement data to measure progress in student learning and to help it identify strategies to improve student achievement and well-being. In terms of accumulating credits and graduating, the report found that specific groups of students, especially Indigenous students and students with special education needs, continue to experience unequal outcomes.

Curriculum and instruction

Key findings and recommendations

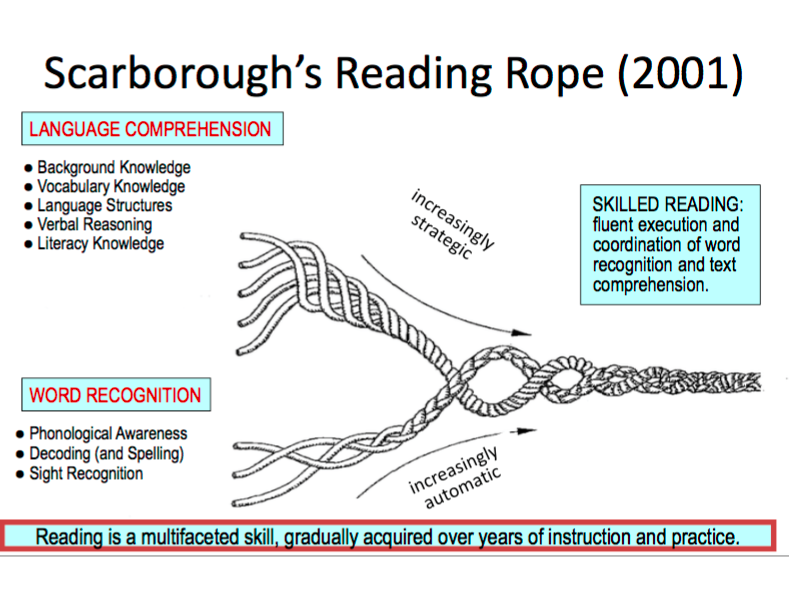

The goal of reading is to understand and make meaning from what is read. The evidence is clear that good reading comprehension requires being able to read words accurately and quickly, or automatically. It also requires good oral language comprehension, including strong vocabulary and background knowledge.

Strong word-level reading is a key foundational skill for becoming fully literate. It is also the skill where most students with reading acquisition difficulties struggle. Students with dyslexia, and many others, do not develop a strong foundation in word reading, setting them up for further academic struggles and potentially, a lower quality of life.

If classroom instruction is based on an evidence-based core curriculum, most students (80–90%) will learn to read words accurately and efficiently, and few students will need more intensive instruction or intervention. Decades of multidisciplinary research has shown that the best way to teach all students to read words is through direct, explicit, systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills. Beginning in Kindergarten, this includes explicit instruction in phonemic awareness [the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds (or phonemes) in spoken words], phonics (which teaches letter-sound associations, also known as grapheme-phoneme correspondences and using these to “sound-out” words and to spell words). From about Grade 2, explicit instruction focuses on more advanced knowledge and skills, such as increased study of word structures and patterns (for example prefixes, word roots and suffixes), and how word spellings relate to one another. From beginning to teach these decoding skills, students also practice reading words in stories to build word-reading accuracy and speed.

Unfortunately, the current Ontario Curriculum, Language, Grades 1–8, 2006 (Ontario Language curriculum) and teacher education in Ontario’s faculties does not promote these highly effective approaches to early word-reading instruction. Instead, with few exceptions, the main approaches in Ontario are teaching word-solving skills with the three-cueing system and balanced literacy. The three-cueing system encourages students to guess or predict words using cues or clues from the context and their prior knowledge. In balanced literacy (or comprehensive balanced literacy), teachers “gradually release responsibility” by first modelling text reading, sharing text reading, then guiding students’ text reading, with the eventual goal of the student reading texts independently. These approaches for word reading are rooted in a whole language philosophy which suggests that by immersing children in spoken and written language, they will discover how to read. Given this philosophy, many of the other important literacy outcomes beyond word-reading skills may also not receive adequate explicit, evidence-based instruction.

With few small exceptions, Ontario students are not being taught foundational word-reading skills using an explicit and systematic approach to teaching phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding and word reading fluency. Even where boards or teachers are trying to be more intentional about using direct, systematic instruction, they are constrained by the current Ontario curriculum and emphasis on cueing systems and balanced literacy.

Many leading reading reports, teachers and teacher federations have recognized the need for teachers to be well prepared and supported to deliver an evidence-based core curriculum, including teaching foundational word-reading skills. Currently, teacher education and professional development places little emphasis on how skilled reading develops and how to teach word reading using direct and systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills. Teachers also learn little about evidence-based early screening and reading interventions, or how to identify and effectively respond to struggling readers.

| The OHRC recommends the Ministry work with an external expert or experts to revise Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, Language curriculum and related instructional guides to remove use of cueing systems for word reading and instead require mandatory explicit, systematic and direct instruction in foundational word-reading skills [Recommendations 27 to 30]. This should be done on an expedited basis while the Ministry and boards simultaneously take immediate steps to align their instructional approaches with the OHRC’s findings and recommendations [Recommendations 31, 33, 39 to 41]. |

|

The OHRC recommends that teacher education programs address the importance of word-reading accuracy and efficiency for reading comprehension; how accurate and efficient word-reading develops; how to teach foundational word-reading and spelling skills in the classroom and the importance of teaching foundational word-reading skills to promote equality for all students [Recommendation 48]. The OHRC further recommends that teacher education programs better equip teachers who are qualified to teach Kindergarten to Grade 6 to deliver the critical components of word-reading instruction and identify, instruct and support students with word-reading difficulties [Recommendations 49 to 55]. |

| The OHRC recommends the Ministry work with an external expert or experts to develop a comprehensive, sustained and job-embedded in-service teacher professional learning program and resources that address reading instruction and how to identify, instruct and support students with word-reading difficulties [Recommendation 56]. |

| The OHRC recommends the Ministry provide adequate funding to implement these recommendations [Recommendations 42, 43, 45, 57, 58]. |

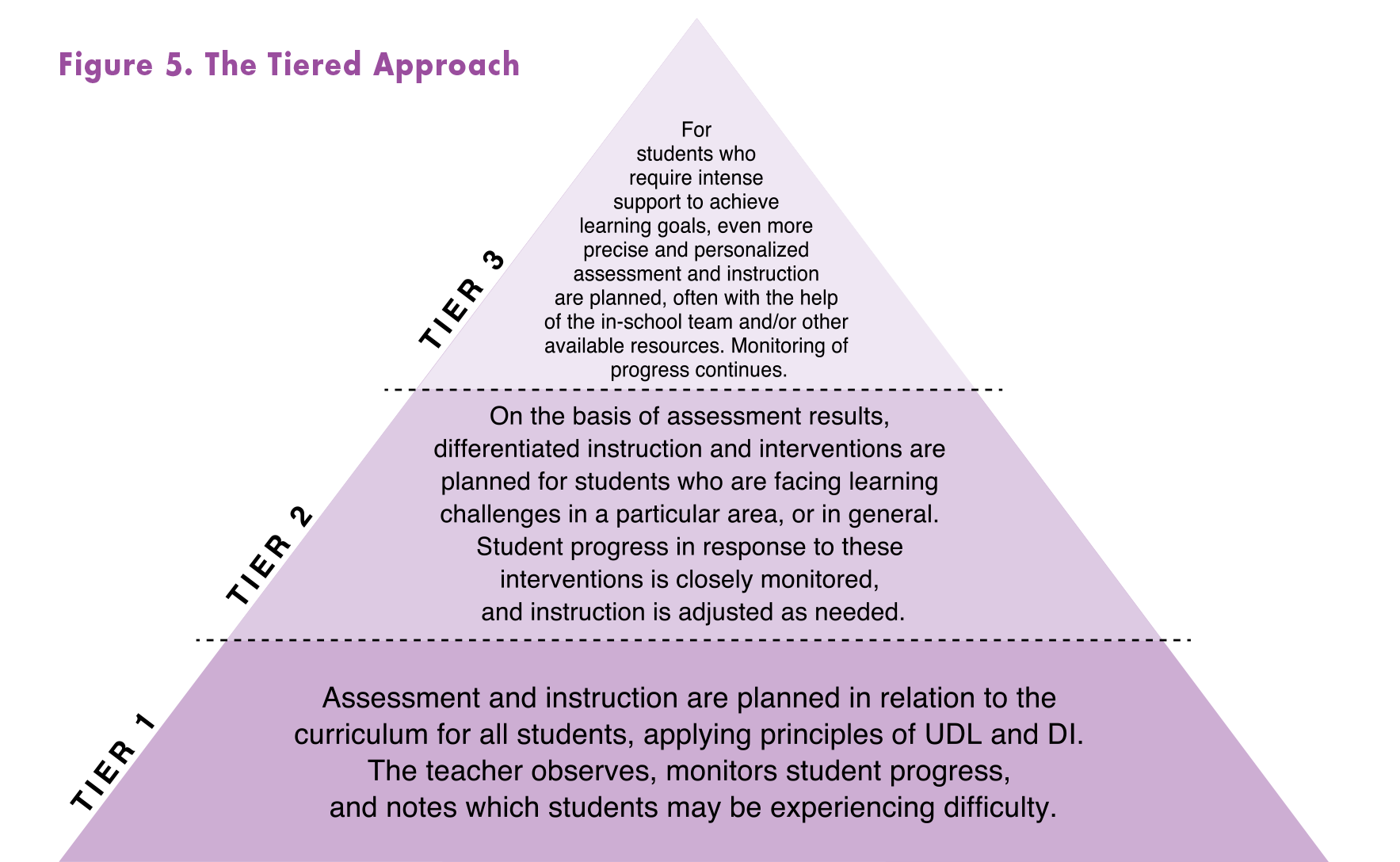

Curriculum and instruction are the foundation for reading success

Science-based curriculum and classroom instruction are the foundation for meeting the right to read. In the education field, a widely accepted framework to support student success is a three-tiered approach to instruction and intervention (also referred to as Response to Intervention or RTI or a Multi-tiered System of Supports or MTSS). This approach is intended to maximize outcomes for all students, not just students with reading disabilities. Tier 1 is the core curriculum that all students receive in the classroom. Meeting the right to read requires high-quality tier 1 classroom instruction using an evidence-based, scientifically researched core curriculum. This would meet the needs of about 80 to 90% of students.

Teachers play a vital role in meeting the right to read. In 2003, Ontario’s own expert panel on early reading said:

Teachers make a difference in the success of their students when they hold a fundamental belief that all children can learn to read and when they have the skills and determination to make it happen.

Teachers must have sufficient and ongoing professional development to deliver a high-quality science-based tier 1 core curriculum as designed. Many leading reports have stressed the importance of teachers being equipped with the skills and knowledge to deliver evidence-based reading instruction, including that needed for teaching foundational word reading skills. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), a union of education professionals, has recognized the importance of preparing teachers to deliver science-based reading instruction both for student outcomes and to empower teachers and support their professionalism and autonomy.

The AFT worked with Dr. Louisa Moats to publish a report, Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science, 2020, that translates the latest research in this area into information for educators. Several Canadian studies have shown the power of effective teaching to reduce the number of children experiencing reading difficulties. So, it is vital that faculties of education prepare teachers with these skills, and that teachers receive ongoing support and professional development.

Structured literacy is the most effective way to teach early reading

There is an enormous body of settled scientific research on how children learn to read and the most effective way to teach them. Significant reports summarizing this research include reports from Ontario (the Ontario Expert Panel Report on Early Reading) and Canada (the Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network Report), as well as international reports (the National Reading Panel Report in the United States and the Rose Reports in England). The reports all endorse explicit and systematic instruction in the foundational skills that will lead to efficient word reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, including decoding and spelling words, and practice with reading words in stories to build word-reading accuracy and speed (structured literacy).

The goal of reading is to understand and make meaning from the text. The evidence is clear that one essential component of good reading comprehension is the ability to decode or read words quickly and efficiently. So, for students to understand what they read, they must learn to decode, to turn written words into the corresponding spoken word. Learning to decode our alphabetic system requires knowing letter-sound relationships (grapheme-phoneme correspondences) and being able to apply that knowledge to blend the individual sounds together to successfully identify written words (decoding).

When students are explicitly taught and practice skills involved in decoding words, the process becomes quicker and with practice, supports automatic word reading.

Poor decoding skills act as a bottleneck to good reading comprehension. When a student must put a lot of time, effort and attention into reading words, it interferes with the flow of language in the text and uses up mental resources making it harder to understand what is read. Vocabulary and background knowledge, the ability to understand spoken language, and the use of reading comprehension strategies are all also critical aspects of reading development. Indeed, the National Reading Panel found critical roles for instruction in each of the Five Big Ideas in Beginning Reading – phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension.

The best way for students to gain word-reading skills, beginning in Kindergarten, is with explicit and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, and word-level decoding, learning grapheme-phoneme correspondences and how to use these to decode words, including blending sounds and segmenting words into sounds to read words and segmenting words into sounds to write words. Explicit instruction includes more advanced skills as children progress, such as studying word structure and patterns (for example prefixes, word roots, suffixes). This explicit, systematic approach based on reading science is also referred to as structured literacy.

Ontario’s current approach is based on ineffective cueing systems and balanced literacy

Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, 2016 and Grades 1–8 Language curriculum, related Ministry guides for reading instruction, board resources, and teacher education provided by Ontario faculties of education emphasize teaching early reading skills using cueing systems for word solving and balanced literacy. Cueing systems encourage students to predict or guess words using cues or clues based on context or prior knowledge. In balanced literacy, or similar comprehensive balanced literacy approaches, teachers “gradually release responsibility” from modelling reading texts or books, to shared reading with students, to guiding students’ text reading, to students being able to read texts independently.

Cueing systems and balanced literacy for word reading are consistent with a whole language philosophy which assumes that children will “discover” how to read through exposure to spoken and written language. In these approaches, students receive little or no direct, systematic instruction in the building blocks of written language such as phonemic awareness and phonics and how to use these skills to decode words. For example, in Ontario’s current system, it is more likely that a student will be encouraged to predict a word from a picture in the text or guess at a word from the sentence or story context and first letter rather than being taught the sounds that letters and letter combinations represent and how to use that knowledge to “sound out” the word.

Balanced literacy or comprehensive balanced literacy approaches, cueing systems and other whole language beliefs and practices are not supported by the science of reading. They have been discredited in many studies, expert reviews and reports on teaching all students to read words. Cueing systems and balanced literacy approaches are ineffective for teaching a significant proportion of students to read words, and may be most detrimental for students who are at risk. Students most at risk for reading failure, including students with reading disabilities and many students from other Code-protected groups, will not develop critical early reading skills when these approaches are used in schools.

When schools fail to teach students how to read words accurately and fluently, students will find it more difficult to understand and make meaning from what they read. They will be at greater risk of future academic difficulties and other negative consequences. Even students who can catch on to early reading when these approaches are used, may benefit in their fluency and spelling from direct and systematic instruction.

The current core curriculum in Ontario is the Language curriculum. It sets out what all teachers are expected to teach and what every student is expected to learn in each grade. The curriculum is an important tool for establishing mandatory requirements and consistency across the province. Pre-service and in-service teacher education and professional development is largely based on the Ontario curriculum.

The Ontario Language curriculum emphasizes the three-cueing system as the primary approach to teaching students to read words. It explains that this involves looking for clues to predict or guess words based on context and prior knowledge. The overall expectation for each grade is that students will be able to “use knowledge of words and cueing systems to read fluently.” Although it defines phonological awareness, phonemic awareness and phonics in a glossary, the curriculum does not require these to be taught, or provide guidance on how they should be taught.

The inquiry reviewed the literacy component of Ontario’s Kindergarten Program as it relates to decoding and word-reading development and also found it lacking. The program does not pay enough attention to instruction in foundational word reading skills. There are references to phonological awareness, phonemic awareness and phonics in several specific expectations, but there is little discussion of the importance of these skills. There are no clear sets of reading skills that teachers are expected to teach and students are expected to learn. There is not enough information on teaching alphabetic knowledge and decoding skills, including no mention of daily phonics instruction. Also, the Kindergarten program does not discuss the importance of monitoring students’ skills in these areas, or supporting students who are struggling in developing these early reading skills.

Ontario’s teaching guides such as A Guide to Effective Instruction in Reading, Kindergarten to Grade 3, 2003 also promote cueing systems as the main way students gain word-reading skills. The guides provide more detail about how cueing systems should be used. Although phonemic awareness, phonics and word study (which the Guide defines as an instructional activity where students practise recognizing high-frequency words and learn word-solving strategies) are mentioned, the focus is on three-cueing throughout. Even within the discussion of phonemic awareness, phonics and word study, guessing strategies are promoted.

Board-level resources also emphasize cueing-system and balanced literacy approaches. All boards reported following the Ontario Language curriculum and relying on Ministry resources, particularly A Guide to Effective Instruction in Reading, Kindergarten to Grade 3, 2003. The boards said that in addition to cueing systems, they use either a balanced literacy or comprehensive (balanced) literacy approach to teach early reading. In responses to the educator survey, most educators also identified balanced literacy as the predominant approach to teaching reading in Ontario.

With a few small exceptions, boards do not promote an explicit and systematic approach to phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding and word reading fluency. Few board resources referenced phonemic awareness or phonics. Where these were mentioned, there was not enough detail on how to teach and integrate them into an effective approach to early reading instruction. Teachers may deliver some short “mini lessons” on aspects of early reading skills, usually with small groups of students at the teacher’s discretion. However, this ad hoc approach is not the same as evidence-based tier 1 systematic and explicit whole class instruction in foundational word reading skills.

A few boards have recognized the need for more science-based early reading instruction. They have tried to incorporate more explicit instruction in some foundational skills. However, even where boards or teachers are trying to be more intentional about using direct, systematic instruction, they are constrained by the current Ontario curriculum and emphasis on cueing systems and balanced literacy. There are other barriers such as a lack of guidance on and consistent access to evidence-based teacher-friendly resources that would help teachers become knowledgeable about and implement a science-based approach in their classrooms. There are also significant issues with ongoing access to effective professional development.

The inquiry also found another barrier is that some people in the education sector are resistant to change and hold strong beliefs supporting whole language philosophies.

Teachers are not given sufficient education and support

Currently, Ontario teachers are required to deliver a curriculum that is inconsistent with a science-based core curriculum that meets the right to read. They also learn very little about how skilled reading develops and how to teach word reading using proven approaches/structured literacy in their pre-service and in-service education and professional development.

Ontario faculties of education are required to prepare teachers to teach the Ontario curriculum and Kindergarten Program. The inquiry found that pre-service teacher education courses and in-service Additional Qualifications (AQ) courses in reading also focus on ineffective cueing systems and balanced literacy approaches (and discovery and play-based approaches in courses about Kindergarten). There is little time or instruction on making sure pre-service teachers understand general language and early reading development.

Faculties also often emphasize socio-cultural perspectives and culturally responsive pedagogy. These are important in broader discussions about literacy and equity in education, but not a substitute for preparing teachers to deliver direct and explicit instruction in foundational word reading skills. This lack of a strong focus on scientifically supported early reading instruction may be harmful to many historically marginalized student populations and contradict the goal of promoting equity.

The inquiry found that teacher education programs and AQ courses on reading and special education include little about direct and systematic instruction in foundational word reading skills. Future and current teachers are generally not taught how skilled reading develops, including the importance of strong early word-reading skills for future reading fluency and reading comprehension. Teachers do not adequately learn how to teach phonemic awareness, phonics and decoding, and word-reading efficiency. They learn little about early screening to identify at-risk students and about evidence-based interventions. Even teachers who take AQ courses specializing in reading and special education are not learning these skills and how to identify and effectively respond to struggling readers. They are also learning very little, if anything, about reading disabilities and the term dyslexia is rarely used.

Boards said that new teacher graduates have little base knowledge about early reading instruction, so boards must provide this training through New Teacher Induction Programs. Many teachers confirmed they had not learned about effective reading instruction and reading disabilities in their teacher education program or AQ courses. They must seek out this knowledge elsewhere, often by spending their own time and money on research, resources and private training programs.

Boards and teachers also reported challenges with job-embedded professional development. They said that the province’s approach to professional learning has shifted away from comprehensive, ongoing, in-person professional development. The inquiry heard that lack of funding and release time from teaching has hampered job-embedded professional learning.

The inquiry reviewed the boards’ training on reading instruction and other inquiry areas such as screening, and found it focused mostly on specific board programs, resources or assessment methods that are inconsistent with science-based approaches. The knowledge and expertise to deliver professional development based on reading science is not often found within boards, so when training has been provided it has mostly been on ineffective approaches and programs boards are currently using. Two of the inquiry boards appear to be trying to broaden their professional development and to support all Kindergarten to Grade 3 classroom teachers in explicit and systematic instruction in foundational word reading skills. However, this should not be left to the discretion of individual boards, and professional development should be consistent across the province. All Ontario boards will benefit from additional resources, direction and support from the Ministry.

Teachers told the inquiry they want a Language curriculum and professional development that will allow them to reach all students. They also want consistent approaches to teaching reading at the board, school and classroom levels. They said that they will benefit, and their students will benefit. Teachers don’t want to see their students struggle and want to be empowered and supported in exercising their professional judgment to teach their students within an evidence-based and adequately resourced system. The findings and recommendations in this inquiry are consistent with that goal.

Early screening

Key findings and recommendations

A screening measure or instrument is a quick and informal evidence-based assessment that provides information about possible word-reading difficulties. It identifies students who are currently having or are at risk for future word-reading difficulties so they can receive more instruction or immediate intervention. All students should be screened using standardized evidence-based screening measures twice a year from Kindergarten to Grade 2.

Ontario does not currently have universal, systematic, evidence-based early screening to identify at-risk students who need additional instruction and immediate interventions. The current approach is inconsistent, ad hoc and relies mostly on non-evidence-based reading assessments. This leads to many at-risk students not being identified and receiving intervention early enough or at all.

Many students’ reading difficulties are not being caught early, which has significant consequences. Age four to seven is a critical window of opportunity for teaching children foundational word-reading skills and is when intervention will be most effective. Many students who are not progressing as expected in reading are falling through the cracks and are not getting timely interventions and supports. Parents who express concerns are sometimes told not to worry as delays are developmentally normal or even expected for some students (for example, boys and students born late in the calendar year). These misconceptions further contribute to harmful delays as the longer schools wait, the harder it is to close reading gaps. Universal screening reduces the potential for misconceptions and biases to affect decisions about students.

Ontario must address its inadequate approach to early screening, which creates unnecessary conflict and confusion between school boards and teachers, and neglects the best interests of at-risk children. The research on screening for early reading skills is advanced, the financial cost is minimal and the impact of current practices on students is harmful.

| The OHRC recommends the Ministry work with its external expert(s) to mandate and standardize evidence-based screening on foundational skills focusing on word-reading accuracy and fluency. The Ministry should require boards to screen every student twice a year from Kindergarten Year 1 (formerly known as Junior Kindergarten) to Grade 2 with valid and reliable screening tools, and provide boards with stable, enveloped yearly funding for screening. The tools that are selected should correspond to each specific grade and time in the year (in other words, they should measure expected knowledge for that grade and point in time in the school year). The selected screening tools should have clear, reliable and valid interpretation and decision rules [Recommendations 59 to 61]. |

| The OHRC recommends that the results of early screening be used to identify students at risk of failing to learn to read words adequately, and to get these children into immediate, effective evidence-based interventions [Recommendations 60 to 62]. |

| The OHRC recommends teachers be given adequate professional development to effectively implement screening [Recommendation 66], and given the necessary time to complete these assessments [Recommendation 67]. |

Universal screening better ensures early identification and intervention

Along with science-based core curriculum delivered by adequately prepared educators, universal evidence-based early screening is a critical part of tier 1. This screening identifies students who are at risk for reading difficulties or are not responding to evidence-based instruction as expected, which means they are not gaining the required reading skills and knowledge. Early screening makes sure students are identified and receive the programming they need before they start to experience significant difficulties. If done properly and combined with evidence-based instruction and interventions, early screening reduces the likelihood that a student will later need professional assessment by a psychologist or speech-language pathologist. Although beyond the scope of the report, early measures can also be used to screen for difficulties in oral language development.

Screening should be universal. Every student should be screened using common and standardized evidence-based screening measures twice a year from Kindergarten to Grade 2. Evidence-based screening measures supported by research have strong internal and external validity, reliability, and have been linked to the science of reading instruction and how students acquire foundational reading skills. Many screening measures have been rigorously developed and studied, and validity and reliability for predicting risk for reading difficulties is known.

Students in each grade should be screened with specific screening instruments that will measure the expected reading development at that point in time. For example, Kindergarten screening should include measures assessing letter knowledge and phonemic awareness, but by Grade 2 screening should include timed word and passage reading.

Universal screening is important to protect the rights of all students, particularly students from many Code-protected groups. Mandatory instead of discretionary screening reduces the risk of bias in assessment or selecting students for interventions. It reduces the risk that students will fall through the cracks. Universal evidence-based screening ensures better decisions about which students need additional support and ultimately improves student outcomes. Data collected from screening is also valuable for board planning. Boards can compare results from common screening tools across schools or groups of students and direct resources where they are most needed.

Barriers for students learning in French

All students can learn French given the appropriate supports. However, the inquiry heard that students with reading difficulties do not receive equal access to French-language education. French-language rights-holders reported giving up their right to have their child receive a French-language education and moving their child to an English board because French boards have fewer resources and programs for reading difficulties. Students may be discouraged from enrolling in French Immersion, or be encouraged to withdraw, due to misconceptions that students who struggle to learn to read should not learn English and French at the same time. Some parents reported being told the school board does not offer supports such as accommodations and interventions in French Immersion.

A preventative approach is also needed for students learning in French and at risk for reading disabilities. Early scientifically validated screening and evidence-based interventions should equally be implemented within French-language instruction.

Ontario’s approach to early screening is failing many students

As currently interpreted, the Ministry’s Policy/Program Memorandum (PPM) 155 is a significant obstacle to universal early screening. PPM 155 leaves the frequency, timing and selection of students and screening instruments to each teacher’s professional judgment. It prevents boards from requiring that all students be screened at certain times of the year with a common evidence-based screening instrument. This has led to inconsistencies and gaps and a lack of an effective, student-centred approach to early screening. It has also limited boards’ ability to collect data centrally and use it to make decisions.

The inquiry found that screening practices vary by board, school or teacher. There are also significant issues with current screening approaches which compromise the effectiveness of the school boards’ tiered approaches. A teachers’ association representative said the current approach to who gets screened, when and how is based on “a huge amount of luck.”

Most school boards are not implementing universal screening measures at several points in time from Kindergarten to Grade 2. Typically, screening only happens once, usually in Kindergarten Year 2 (formerly known as Senior Kindergarten). Not all students are screened as some educators only screen students they believe are struggling.

When screening happens in Year 2 it is most often with tests that only measure letter-name or letter-sound knowledge and/or phonological awareness. Only some aspects of phonological awareness are typically evaluated. These skills are very early pre-literacy skills, and only some of what should be assessed. Boards often mistakenly believe these basic Year 2 screeners are complete screening assessments of all the knowledge and skills for word-reading acquisition. A few boards re-administer the same screener or a slightly different one that sometimes includes some more advanced skills at a second and/or third point in time to the same students who performed poorly the first time. This misses students who performed well when screened on early literacy skills, but later struggle with more advanced skills such as reading accuracy or fluency.

After Kindergarten, boards typically assess students using reading assessments associated with commercial reading programs that align with three-cueing and balanced literacy instructional approaches. These are not evidence-based screening instruments. Teachers typically use observational tools such as a miscue analysis or running record where a student reads aloud from a levelled reader and the teacher observes the student’s reading behaviours including the words they read correctly, how they are using the three-cueing system to predict words, and their mistakes. These methods are not useful measures. They only tell the teacher if the student is significantly below grade level in their ability to read levelled readers, not how the student is progressing on foundational word reading skills. These assessments fail to identify many children at risk for word-reading failure.

Some boards did include evidence-based screening tools on their lists of “approved” screening tools. However, because of PPM 155, there is no guarantee that teachers will pick these assessments and boards could not confirm if they are being used. Some boards use board-developed assessments which have some good components but not all necessary elements, and they do not appear to have been adequately assessed to make sure they are effective.

The inquiry also found that boards could not provide clear information about how the results of screening are used, or do not know the best way to respond to the information from screening.

Establishing a standardized approach for universal evidence-based early screening

Ontario needs to standardize early screening and make it universal and based on the reading science. This includes stipulating that all students must be screened, when, how often, and with what screening instruments. Educators and other school professionals such as board speech-language pathologists and psychologists should be an integral part of developing this approach.

Educators administering the screening should be given adequate professional learning on the basic principles of early reading screening measures and knowledge about the specific tools that will be used. Experience from other jurisdictions that have implemented successful early screening programs indicates screening students takes 10–15 minutes per student. Educators must be given adequate time to do this important work, including recording the data from screening.

The screening tools selected should be standardized for consistency, and must be evidence-based, include the appropriate measures for each grade, and be administered to every student twice a year from Kindergarten to Grade 2. Boards should use a consistent system to record each student’s screening results. The results should be used to identify and provide immediate intervention for students who need it. Collecting data on early screening is also very important, but the data should not be used for performance management or to blame educators for issues related to reading. Boards must also be very careful not to use or report the data in a way that stereotypes or further marginalizes any student, group of students or school.

Communicating with parents is also a key part of successfully implementing early screening. Parents must understand that the screening is universal, their child is not being singled out, and the purpose of screening is to see if their child may need further supports or interventions. Some parents may be concerned that screening could lead to their child being labelled or stigmatized. Boards must explain that screening helps avoid the risk of a student developing a reading disability or needing more intensive special education supports later on.

Screening is an essential part of a systematic and comprehensive approach to meeting the right to read. The earlier we identify students needing more targeted instruction and intervention in foundational word-reading skills, the better. Investing the time and effort to conduct universal early screening and implement interventions will reduce the need for more costly and intensive services in the long run. Students will have better outcomes and educators will be better off when they have reliable and useful information about their students and are in a better position to respond.

Reading interventions

Key findings and recommendations

Many more students will learn to read if we change our current approaches to classroom reading instruction, screen all students and then provide early and tiered evidence-based interventions. Ontario’s approach to reading interventions is deficient resulting in many students failing to learn foundational word-reading skills. When this happens, our education system has failed these students.

Many more students need reading interventions because classroom instruction in word reading is not based on reading science. The need for reading interventions exceeds the available spots. So, many students never receive these interventions in school or receive them far too late.

Intervention is most effective when delivered in Kindergarten and Grade 1, and no later than Grade 2. Yet, in Ontario the most effective interventions are only available, if at all, after Grade 3 or much later. Boards’ first response to struggling readers is often to provide more of the same ineffective reading instruction that has already failed the student, but in smaller groups or one-on-one. If a more formal intervention program is available in the earliest grades, it is almost always one of the several ineffective commercial programs that do not have a solid research base in building foundational word-reading skills. A critical window of opportunity begins to close, and students fall further and further behind.

There are a few exceptions where boards do have good programs for the youngest students, but once again, demand outstrips supply. The lack of consistency between boards and schools is concerning. Good early intervention programs should be available to all students, regardless of where in Ontario they go to school or which school they attend in a board.

There are some good intervention programs in the older grades, typically after students have struggled and fallen behind for many years. However, boards appear to lack a systematic and fair way for selecting students. Parents who can advocate or can pay for a private psychoeducational assessment are more likely to secure a spot for their child. Although boards may have some measures to assign students to programs, they are typically problematic such as requiring the student to be several years behind based on unreliable book-reading levels. Many students’ needs go unmet due to limits on how many can be offered reading interventions.

| Ontario needs to decrease the need for reading interventions by using explicit, systematic instruction in foundational word-reading skills in the classroom while simultaneously increasing access to proven interventions beginning in the earliest grades. To do this, the OHRC recommends the Ministry work with an external expert or experts to select appropriate early (Kindergarten and Grade 1) and later (Grades 2, 3 and onwards) interventions that school boards must choose from. These interventions should be evidence-based and include systemic, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics and building word-reading accuracy and fluency [Recommendation 69]. |

| The OHRC recommends school boards immediately stop using reading interventions that do not include these components or have a strong evidence base for students who struggle with word reading, and students at risk for or identified or diagnosed with reading disabilities or dyslexia and only use interventions from the Ministry’s list [Recommendation 70]. |